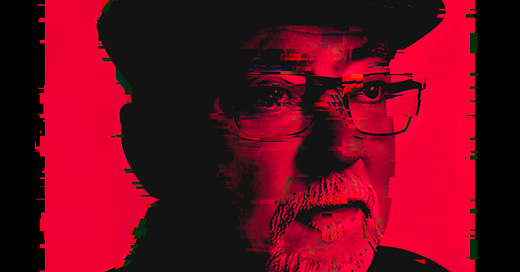

James (‘Jim’) Coyne was an occasionally brilliant psychologist who used public accusations, frivolous lawsuits, and strategic lies to inflict emotional pain and professional harm on other scientists—especially those early in their careers. By the time he died, a little over a month ago as I write this, he was almost universally feared. His personality met the freedom and access of virtual social networks the way cesium meets water, to the detriment of all.

I first met Coyne in the late 1990s. He was passing through Tucson and I managed to snag some of his time. I peppered him with questions about systems theory, radical behaviorism, prescription privileges for psychologists, the social context of depression, and probably other things. He took my questions seriously and left me with plenty to think about. I could see then—and can remember still—why he was such a big deal. He was smart, and his wit—properly contained—was sharp and entertaining. His early work on the interpersonal theory of depression was seminal— innovative and essential to expanding our understanding of mental health as deeply embedded in interpersonal relationships. It remains a cornerstone of the field, influencing both theory and practice. It helped shape my own career, too—I was an enthusiast.

We kept in superficial touch off and on until about ten years ago, when he suddenly deemed me to be among his many targets. By then, he’d made a habit of such turns, alienating almost everyone who’d ever worked with him or, for a while, enjoyed his company.

Coyne’s antipathy for me started when he accused my co-author Sue Johnson of failing to disclose a conflict of interest. He was right. ICEEFT, a non-profit organization that promoted Sue’s Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for couples, had paid the neuroimaging bill for the study we’d done together. I had been the corresponding author of the paper in question—not Sue. It had been my job to add the conflict of interest (COI) statement and I had more or less ignored it, having failed to appreciate the relevance of the COI to anything I’d ever done before. When I told Sue that I hadn’t included the COI statement, she urgently requested a correction. The correction was made and Coyne loudly proclaimed a victory. He wasn’t wrong about that, either. His action didn’t merely result in a correction—a good enough outcome—but also caused me, personally, to reflect on why I’d dismissed the COI statement as not relevant in the first place, and that changed how I thought about conflicts of interest generally. I think I’m more thoughtful about such things now and I appreciate the change.

A couple of months later I wrote a blog post called “Negative Psychology,” in which I argued that social media had encouraged a tendency in scientific criticism toward crummy behavior. This was a response to uncharacteristically vitriolic discussions I observed during the 2014 meeting of the Association for Psychological Science. Coyne thought the whole thing was directed at him and was furious. I wasn’t prepared for what followed. He ranted about it on Twitter and Facebook and threatened to write blog posts about it. I had known about but never read his blog before. So I did.

Coyne’s blogs were verbose and erratic, often veering into personal attacks. He freely fabricated conspiracies and leveled baseless accusations that obscured whatever legitimate critiques he might have had. I recognized these as the tactics of the “internet troll.” So I “defriended” him on Facebook and blocked him on Twitter. These actions inflamed him further.

Now that I was acutely on his radar, he devoted several blog posts to my lousy research program. He wanted his readers to know that I was incompetent at best and possibly a fraud. He insinuated much else—I was out to make some quick bucks or something, something, I can’t quite remember. He made up stories about me, inventing a lurid menagerie of conspiracies, sinister motivations, and misdeeds.

I spoke to my old friend and grad school mentor Varda Shoham about it. She’d known Coyne personally for decades. Her advice was to ignore him, noting that she herself had borne the brunt of his manic attacks and knew many others who’d suffered the same. For what it’s worth, she also congratulated me for getting his attention: “You’ve made the Coyne list!” she said. She suggested that a confrontation was exactly what he wanted, and that I shouldn’t give it to him.

And, anyway, although Coyne’s bilious ravings were not bereft of signal, the signal to noise ratio was low enough to preclude any serious engagement. Who has time to push against all that wind? Moreover, it wasn’t a situation where all parties were prepared (or sufficiently dignified) to employ the same rhetoric, which put me at a disadvantage. So I ignored him and that ultimately worked.

* * *

You danced with Jim Coyne at your own risk. Many did, anyway. In some ways I’m more disappointed with them than Coyne himself. It was not a challenge of perception or imagination to see that Coyne was out of control, even though he was capable of staying within the bounds of professional conduct when he had to.

Sitting at a bar with a colleague after the first meeting of The Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science (SIPS), I brought up the problem of Jim Coyne, noting, uncontroversially, that he was a liar and a bully. My colleague said, “yeah but he’s mostly a force for good.” Can you imagine saying that of someone who only occasionally, say, falsified data? Do you think that’s an unfair comparison?

To the degree that falsifying data and spreading lies about colleagues differ at all, it’s only in their target: one distorts what we know about science, the other distorts what we know about scientists. To tolerate habitual lying, even when it comes from someone who occasionally advances good ideas, is to normalize behavior that undermines everyone’s trust, just the way falsifying data does.

And if we excuse unethical behavior because we like or agree with the person committing it, we set a dangerous precedent. Scientists should demand both intellectual rigor and personal integrity—not one at the expense of the other.

The thing about bullies is that “bully” inevitably becomes their most salient attribute. It doesn’t take long for the lumbering emotional bulk of bullying to obscure everything else. And Jim Coyne had the potential for much else. It could be tragic, I suppose, but after bearing the brunt of his boorish behavior—and nowhere near the worst of it—a feeling of tragedy is hard for me to muster.

Ultimately, after so many straw men, so many mistakes and mischaracterizations, so many non sequiturs and just-so-stories, Coyne’s essays started slowly if accidentally to constitute their own counter-argument. Eventually, we all realized that Coyne routinely—habitually, compulsively—committed every rhetorical crime he accused others of. And so, like a self-limiting chemical reaction, he wound up debunking no one so much as himself.

* * *

Like it or not, and I don’t, Jim Coyne’s death marks the end of an era in psychological science—an era shaped in part by his uniquely destructive behavior. It’s customary, for good reasons, to refrain from a critique like this after someone’s death—especially when the death was so recent. But I thought it was important for someone to frankly reflect on what the field has been through with him. I’m reluctant to speak ill of the dead, too, but I won’t hesitate to speak ill of lies and bullying as a means of coercing colleagues.

Coyne’s tactics caused immense and unnecessary harm, not only to individuals, which is bad enough, but also to the norms of scientific discourse. As scientists, our most vital responsibility is to critique each other’s work. Coyne showed us how not to do it, and our reckoning with that is overdue, not least because few—including myself—were willing to do so during his lifetime, out of fear of becoming a target. Even those who knew better—often those closest to him—recognized his lies and bullying for what they were and remained silent. That silence, while understandable, allowed his tactics to continue and even proliferate, leaving his victims with little recourse. Now, in his absence, it’s critical that we confront his true legacy head-on.

Yes, it’s true: criticism is the best way to refine ideas, challenge assumptions, and advance knowledge. But Jim Coyne’s approach to criticism was outside of that process, and even opposed to it, because his tactics silenced dialogue, stifled creativity, and turned spaces that could foster constructive conversation into scorched-earth battlegrounds. Coyne didn’t foster progress. He fostered fear and broken trust.

Ironically, we can turn Coyne’s legacy into a useful cautionary tale, by recommitting to a norm where criticism serves as a tool for refinement and collaboration instead of a weapon for harm. This means holding ourselves and each other accountable for the way we criticize—ensuring that our critiques are fair, evidence-based, reasonable, and free of the personal animosity at the heart of Coyne’s work. In this way, Jim Coyne’s death offers us an opportunity not only for reckoning, but also renewal.

Thanks for writing this Jim. I dared to defend you and that put me on his list. And boy did he come after me. He contacted HR at my university to say that I verbally attacked him on Twitter and should be fired for physically threatening an "old man." When they asked for proof, his screen shots showed nothing of the sort. They contacted me to tell me about it and to avoid him as he is costing the university money to investigate his nonsense.

He really, really despised well-being science and then tried to peddle self-published books on the topic.

My first interaction with him at dinner in New Orleans with Bonanno, McNally, Frueh, and a few others was a delight. He had such a great mind. As you said - what a waste of great critical thinking to aim it toward harming people than producing good work.

Thanks for this piece, Jim. I, too, have been one of Coyne's targets. Just in case anyone might be interested, I'll share my story, noting for the record that I previously had had a cordial relationship with Jim for any number of years and greatly appreciated his incisive mind. Coyne and I were both members of the Society for the Science of Clinical Psychology (SSCP) and on its listserv, a site of vigorous debate. Not surprisingly, Coyne took the debate to a new level, such that he was clearly in violation of the listserv's posting policies. However, the Society had no formal means to do anything about such behavior other than remind people of the policy to which Coyne, again not surprisingly, did not take kindly. So, when I happened to be elected President, I decided to take action and proposed a process for removing recurrent violators. After much spirited debate on the listserv about where to draw the line between freedom of speech and unacceptable behavior, through which my initial proposal was considerably revised, tightened up, and greatly improved, by adding multiple chances for people to improve their behavior, and a rather legalistic process for ultimately removing a member from the listserv, the membership voted on implementing it, and it passed by a wide margin. Then came the process.... I've already gone on too long, so I'll spare everyone the details, but I carefully documented every step along the way, through which I was repeatedly attacked and vilified by Coyne, yet again unsurprisingly. The document ultimately came to 27 pages and Coyne was removed from the listserv, after which he used multiple opportunities to continue to excoriate me for his removal. Fast forward a decade or so, and Coyne asked to be reinstated to the SSCP listserv. Fortunately, there was enough institutional memory that the then-SSCP Board contacted me about what had occurred previously and I'll just say that I was really glad to have compiled and saved that document.